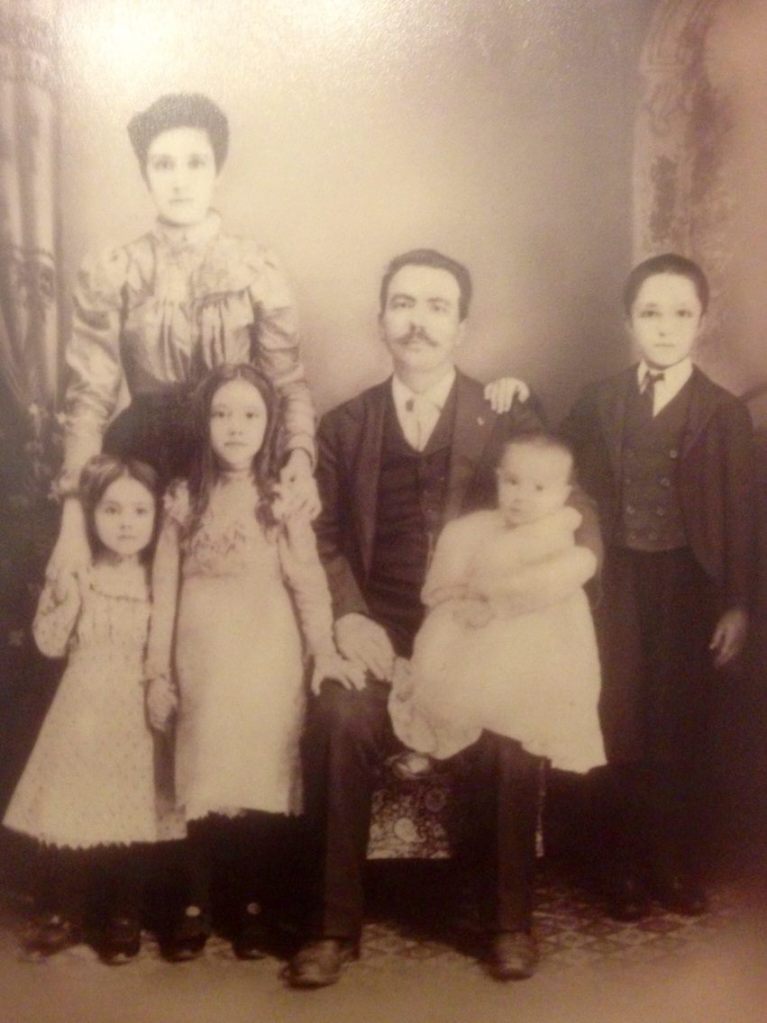

On December 20, 1923, I entered this world as the third daughter born to Alvina and Vincenzo “James” Chimenti. I was born at home with the assistance of a midwife, as was the custom in those days.

My grandmother, who everyone called “Mama Damis,” owned the four-family apartment building in Brooklyn where I was born. Uncle Pete and Aunt Helen lived on the first floor, Mama and Papa Damis on the second floor, Aunt Lizzie and Uncle Johnny on the third floor, and we lived on the fourth floor.

My brother Jim was born 18 months after me. He and I were very close. I even went to his high school prom with him in 1944. My high school had cancelled my prom two years earlier, as all the neighborhood boys had just left for war in the spring of 1942.

As a young boy, Jim was sickly. Mom seemed to always dote on him and give him special care, especially after he had whooping-cough. She gave him the cream from the top of the milk bottles along with vitamins, eggnog, and cod liver oil. (She never could get any of us girls to take the cod liver oil.)

I, on the other hand, was a very active child and hardly ever stopped moving. I can remember running up and down the stairs in our apartment building and my dad would tease me saying, “Don’t you ever sit still?”

My father worked in a shoe factory, and he worked long hours. It was reliable work though, because as Dad said, people always need shoes. When Jim was a toddler, my father was offered a position as the superintendent of a shoe factory in Malden Massachusetts.

When we first moved to Malden, I missed Mama Damis so much that for once I stopped running and singing. Mama was worried, so she asked Aunt Tillie to come up to Massachusetts and take me back to New York for a visit. We traveled by train. It was exciting but as soon as we arrived in Brooklyn, I became so homesick for my family that my Aunt had to turn around and bring me right back home.

As fate would have it, shortly after this Dad was offered a better position with more pay in Rochester, New York, so again we moved.

As I mentioned earlier, Jim and I were very close in age, and we did everything together. In fact, when one of us got sick, the other one soon followed — measles, chickenpox, mumps, etc. The best part of being sick was that we got a lot of attention. Dad came home with boxes of candy for us and other presents. When Jim and I got the mumps, our parents bought us a white bunny rabbit. We kept it until it grew too big to live in the house, and that is when we met our neighbors, Charlie and Arthur.

Charlie and Arthur lived together in an apartment over a restaurant that they owned. The restaurant, called the Eagle Tea Room, was situated on a large piece of property. In my opinion it was the fanciest and most exquisite restaurant I had ever seen.

Charlie and Arthur kept chickens and rabbits, and they had a beautiful vegetable garden and small orchard. After they took our rabbit, they told us we could go see her whenever we wanted. My father, who loved to brag about the wonderful fruits and vegetables in his native Italy, enjoyed visiting with Charlie and Arthur and talking about their restaurant.

Charlie and Arthur invited our family to pick as much fruit from their trees as we wanted. One day, in cherry season, Dad took us next door and we picked baskets full of cherries — all the while eating as much as we possibly could. We brought the buckets home for Mama to enjoy. She started splitting the cherries and lo and behold every single cherry had a worm in it. She gave us all laxatives and threw away our whole harvest!

Rochester is not too far from Niagara Falls, so our family made frequent trips to the falls with Charlie and Arthur. What a picnic lunch they would pack! We always traveled in Dad’s Essex, which I remember he purchased for $600. It was blue with a trunk on the outside back of the car and a running board. We had never owned a car in the city and Dad was very proud of the Essex. I remember he spent every Saturday morning washing and polishing the car.

We only lived in Rochester for a few years and then we moved back to Brooklyn. I became very busy with church and school and we never made it back to visit. Still, to this day I have such happy memories of Charlie and Arthur and the Eagle Tea Room.